The Mandela Effect: A Conspiracy Theory

Harley Johnson Examines the Mandela Effect

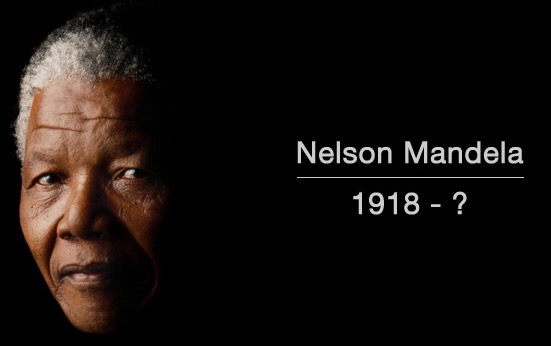

Nelson Mandela, the president of South Africa from 1994-1999, became the catalyst of The Mandela Effect.

October 17, 2016

A large number of people remember anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela dying in prison. Numerous books even stated that he did. However, Mandela was released from jail and did not die in prison, contrary to what is a popularly held belief. This is the Mandela Effect.

According to Snopes.com, rumor research website, The Mandela Effect is a name given to the phenomenon of the collective misremembering of specific facts or events. The official creator, Fiona Broome, states the Mandela Effect is “not a conspiracy theory…it’s related to alternate history and parallel realities” (skepticproject.com).

Another popular example of The Mandela Effect is The Berenstein Bears.

“I remember [the story title as] The Berenstein Bears, but it was actually The Berenstain Bears the whole time,” said sophomore Cameron Rayle.

More examples include Sex in the City, which is really Sex and the City; Looney Toons, which is actually Looney Tunes; and The Flinstones, which is The Flintstones. Some quotes aren’t what society thought they were either, such as “Luke I am your father,” was really “No I am your father.” The Mr. Rogers’ theme song “It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood,” was really “It’s a beautiful day in this neighborhood.” Some product and company names fall prey to this phenomenon as well. Febreeze is actually spelled Febreze, while Chic-fil-A is spelled Chick-fil-A.

American YouTube personality Shane Dawson has created numerous popular videos concerning conspiracy theories. Dawson now claims his favorite is The Mandela Effect.

“I’ve done a video on this before, maybe a year or two ago [after hearing Jenna Marbles talk about it on her Podcast] and it continues to creep me out and blow me away. But since then there’s been so much more evidence and more proof, and more people talking about it, its just become so much bigger,” said Dawson, who has over 7 million subscribers to his conspiracy theory videos on YouTube.

Dawson isn’t the only one who believes in The Mandela Effect. Over 1/4 of Northmont students also agree with him.

“I believe in The Mandela Effect. The entire world can’t be wrong about the exact same thing, [because] it’s improbable,” said sophomore Mary Webb, who is among the 28% of students who accept the phenomenon as true.

According to Edward Winston with The Skeptic Project, the Mandela Effect became semi-mainstream on the Internet in August 2015.

SURGE READERS: What do you think?