What Means are Necessary?

Alexandria Montgomery Explores the Nature of Change

May 9, 2016

Change. It’s that sticky, difficult thing none of us want to talk about despite secretly wishing to actualize all the imagery it brings. Sure, we’d all like to end world hunger, save the polar bears, and stop the constant gunning-down of blacks on the instant replay; but we somehow can’t bring ourselves to take the necessary steps to setting that first domino to fall. While our hearts recognize the eminence, we convince ourselves our conditions — and on a deeper level, our conditioning — disqualify us. The gap between this corn-ridden comfortable suburbia and the starving African kids, polar ice caps, and violent ghettos becomes impossible and we continue to lead our quietly comfortable lives. Deep down we know we could be doing more, but we just… don’t.

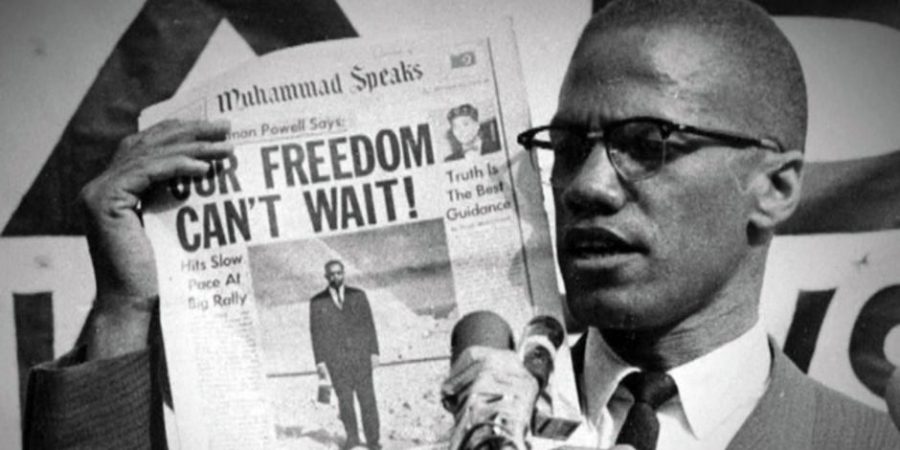

The biggest antithesis of this inactivity was Malcolm X. While it could be argued his activism was more destructive than constructive, there are still valuable lessons to extract from his ethos. Before his time at Mecca, he delivered a speech that sent the country into a fearful frenzy. The verbal clause responsible for the agitation of an entire nation was: “ [We will achieve this change] by any means necessary.” Given the history of Malcolm X and his militant persona, many perceived this political aim as an excuse for violence. The bulk of society obviously is not as militant as Mr. X, but there still is an important lesson we must heed — even amidst his controversy. Maybe we can’t save the world, but we can still ask ourselves what means are necessary — even in face of inevitable opposition — for making the world a better place.

To gain perspectives on change and what it takes to achieve it, I sat with students in Mrs. Brannon’s advanced language arts classes and showed them a video clip of Malcolm X’s speech. I explained that as a class of graduating young millennials, we have extreme problems; but it is coupled with our extreme power. We have more information available to us than any generation before, and we also outnumber the Baby Boomers — one of the most economically and politically influential generations in history. We are in the opportune position to infect our world with intentional shifts. Between discussing this with two periods, two equally distinct views on the world and our role in it emerged. Mrs. Brannon’s second period class took on a pessimistic realism, while third period displayed a realistic optimism. The biggest factor the students felt supported their disbelief in widespread change is the fact that the issues that demand attention aren’t “big” enough for everyone to care. For example, issues such as systemic racism, the prison industrial complex, and debt are pressing — but they only affect people in quiet ways. One student ventured to say that these things are more so “personal problems than national crises”. And while this may be true on some level, the stance that acknowledges an issue but invalidates all aims to alleviate the issue’s effects is not a fruitful stance. This outlook serves no ice caps, ghettos, or starving kids. It only eases any vexations these crises produce, but still prevent the concern from germinating into meaningful action.

Third period, however, held a more positive outlook. They agreed that while there are issues that don’t affect us all, if one person acknowledged and addressed them, their actions would radiate outward and prompt other intentional actions. A few students even agreed with Malcolm X — that in order to make change, certain beliefs must be sacrificed in order to make room for outlooks that seek to benefit all. This optimism was coupled with realism, though. Change is hard to come by, but the trick is to commit ourselves to it. This means smart small, but start now.

One thing both classes agreed on, though, is that there are problems in the world — and that none but us have to responsibility of acting upon those issues. Each stance — be it pessimistic realism or realistic optimism — is valid, but only one preserves the sanctity of humankind by allowing room to enact proper, meaningful change. Likewise, though, you decide.